An Introduction to Quantitative Sports Betting

A comprehensive guide to profitable sports betting. No prior experience required.

Introduction

As a recent college graduate, I’ve noticed many of my friends getting into sports betting. Given that you can’t watch a football game without seeing 500 ads from FanDuel and DraftKings, I’m not surprised. I’m a sports fan who enjoys poker and other games of probability, so sports betting naturally caught my interest. After a few weeks of learning how it worked, I deposited a small amount into my first account to see if I could beat the bookies.

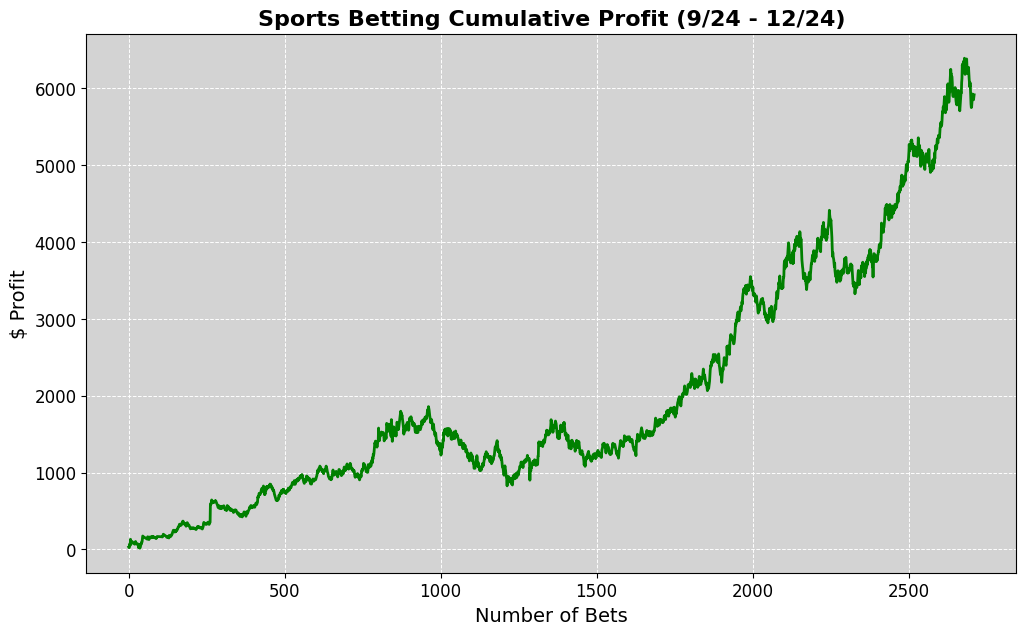

In just three months, I placed over 2500 wagers and made more than \(\$5000\) in profit. These days, some sportsbooks won’t even let me bet more than a few dollars. While that’s a drop in the bucket compared to the volume of professional bettors, I learned a ton about the gambling industry, how betting markets work, and even a bit about sports along the way.

But how do DraftKings and FanDuel make money in the first place? How do people profit from sports betting? In this post, I’ll break down how sportsbooks work and share basic strategies advantage players use to win.

The Vig

Everyone knows that the “house always wins” – but why? Simply put, the casino pays out less than what’s mathematically fair. That built in difference is called the “house edge”, or “vig”.

A simple example

Imagine betting $10 on a fair coin flip. Since the coin has a 50–50 chance of landing heads or tails, what would a fair payout be?

The answer is $20, or more generally, 2x your wager. If you win half the time and lose half the time, a fair payout ensures that, over many bets, your gains and losses cancel out. You neither win nor lose money in the long run.

Mathematically, we say that if the expected value (EV) of a bet is zero, then the bet is fair:

\[EV = P(\text{Win}) \cdot ($ \text{Profit}) - P(\text{Lose}) \cdot ($ \text{Wager})\]Setting \(EV = 0\) and \(P(\text{Lose}) = 1 - P(\text{Win})\), we can solve for the fair payout:

\[\text{\$ Fair Profit} = \frac{(1 - P(\text{Win})) \cdot (\text{\$ Wager})}{P(\text{Win})}\]Where the casino makes money

Of course, casinos don’t offer fair bets. Suppose the casino pays out 1.9x (-111 in American odds) your wager for a win.

If two people each bet $10 (one on heads and one on tails) the casino collects $20 upfront. No matter which side the coin lands on, the casino only pays $19 to the winner, keeping $1 as profit.

Mathematically, a 1.9x payout would be fair only if your chance of winning were \(52.6\%\). This value is known as the implied probability. If we sum the implied probabilities of all outcomes:

\[P_{\text{implied}}(H) + P_{\text{implied}}(T) = 52.6\% + 52.6 \% = 105.2\%\]The extra \(5.2\%\) is the vigorish (also called the vig, juice, or house edge). It’s the sportsbook’s fee for processing bets, and its size varies by market.

Why the vig matters

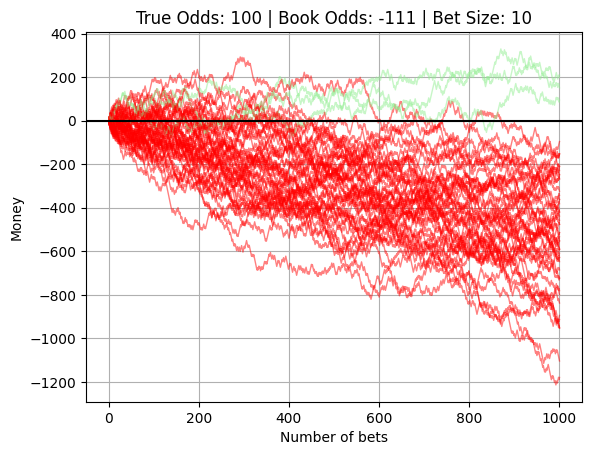

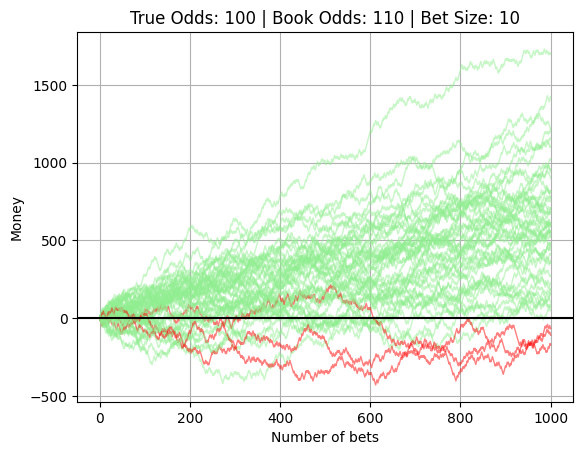

To see the long-run effect of the vig, let’s simulate 50 players betting $10 on this coin flip 1,000 times:

Only 3 out of 50 (\(6\%\)) players ended up profitable! The average final balance was \(-\$494\), meaning the casino earned roughly \(\$25000\)!

Observe that even a small vig makes long-term profitability extremely unlikely.

Example Vig Calculations

Sportsbooks apply higher vigs to markets where they have less confidence, often due to lower liquidity or limited data. Let’s look at two real examples.

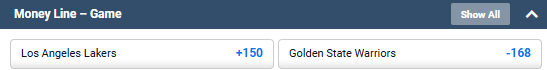

First, an NBA game between the Lakers and Warriors from Pinnacle, one of the sharpest sportsbooks. Since the NBA is a highly popular league with tons of data and heavy betting activity, we expect a low vig:

This line has a \(2.7\%\) vig, indicating Pinnacle has high confidence in its pricing.

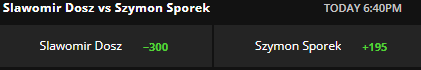

Now compare that to a random table tennis match on DraftKings:

Here, the vig jumps to \(8.9\%\). With less betting volume and weaker data, DraftKings must add a larger cushion to protect against mispricing errors.

Exploiting Market Inefficiencies

Sportsbooks set odds using statistical models, historical data, and input from sharp bettors, creating markets that aggregate public opinion and information. Companies like FanDuel and DraftKings hire experienced analysts and data scientists to price their lines as accurately as possible.

In an efficient market, the odds closely reflect the true probabilities of outcomes, leaving little room for bettors to find an edge. Mainstream markets like NFL moneylines often fall into this category.

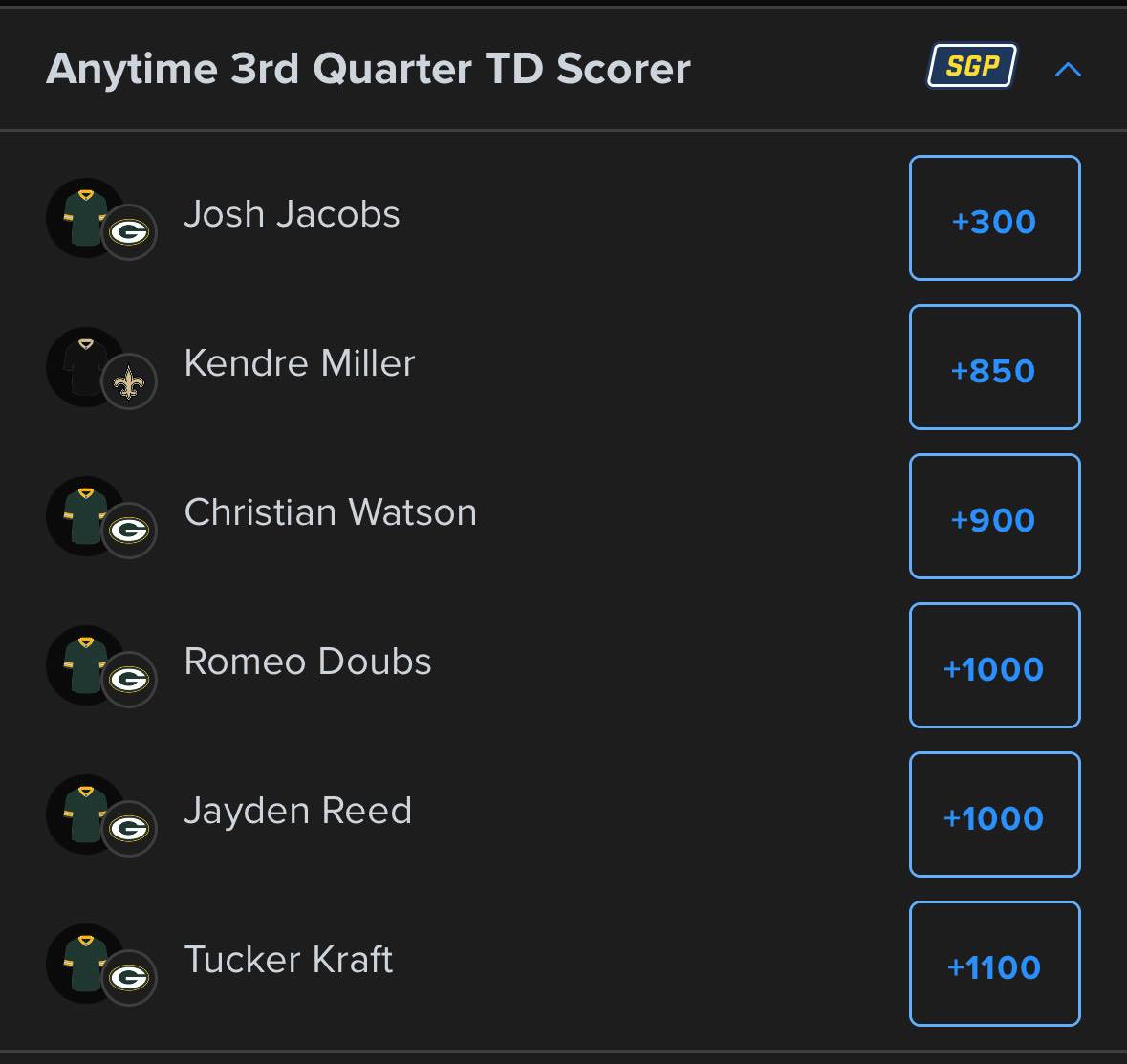

However, sportsbooks aren’t just in the business of accuracy; they’re in the business of engagement. For any given game, they may offer hundreds of additional markets designed to attract casual bettors. These smaller markets are often less efficient:

What creates an edge?

All successful sports bettors make money the same way: by identifying bets where the true probability of winning is higher than what the sportsbook’s odds imply.

To illustrate, let’s revisit the coin flip example. This time, the casino makes a mistake and offers +110 odds (a 2.1x payout):

Now, \(47/50\) (\(94\%\)) of players end up profitable, with an average final balance of \(\$576\). The expected value of this scenario is \(\$500\). The key point is that when the odds imply a lower probability than reality, the bet has positive expected value (+EV).

Of course, coin flips are easy but real sports are messier. So how do bettors estimate true probabilities in practice?

Two approaches to finding value

There are two broad strategies bettors use to identify +EV bets: bottom-up and top-down.

- Bottom-Up: Bottom-up bettors create independent models to predict outcomes, then compare those predictions to sportsbook odds. For example, if a model estimates a team has a \(45\%\) chance of winning, but the sportsbook implies \(40\%\), then the bettor has identified a potential value bet.

- Pros: independent edges, potential for higher returns

- Cons: requires extensive data, domain expertise, and specialization; hard to quantify your edge

- Top-Down: Top-down bettors compare odds across many sportsbooks to find discrepancies. If 20 books offer +100 odds (\(50\%\) implied probability) for a bet while DraftKings offers +110 (\(47.6\%\) implied probability), DraftKings likely mispriced their line.

- Pros: requires minimal sports knowledge, quantifiable edge, leverages sharp market consensus

- Cons: smaller margins, requires constant monitoring, lines move quickly

The most profitable bettors often combine both approaches: bottom-up models to estimate probabilities, and top-down comparisons to find the best available price.

In my case, I relied exclusively on a top-down approach since I didn’t have the expertise or resources to build reliable models from scratch.

Top-down betting requires software to monitor odds across many sportsbooks. One tool I regularly used CrazyNinjaOdds. Many similar services exist (often with higher quality data), but I’d recommend doing extra digging on your own before paying hundreds of dollars per month.

Which sportsbooks should we trust?

Not all sportsbooks are created equal. Broadly speaking, they fall into three categories: market makers, retail sportsbooks, and betting exchanges. Interpreting lines correctly requires understanding the differences between sportsbooks.

Market Making Sportsbooks

Market making books willingly accept bets from sharp bettors and use that action to refine their lines. By incorporating smart money, their odds converge toward a consensus of expert opinion. Their business model prioritizes accuracy and volume, which allows them to offer consistently low-vig lines (essentially the “best prices” available).

Because accuracy matters more than promotion, market makers tend to avoid gimmicks, bonuses, and novelty markets. In effect, their odds represent a crowd-sourced average of sharp models (see: wisdom of the crowd).

For bettors, this is extremely useful: instead of building our own models from scratch, we can treat market maker lines as a reliable estimate of true probabilities (for free!).

The most well-known market making sportsbooks include:

- Pinnacle

- Circa

- Bookmaker

Retail Sportsbooks

Retail sportsbooks are the big names you’ve seen advertised everywhere. Their primary audience consists of the casual bettor unconcerned with odds accuracy. Unlike market makers, retail books focus on marketing and user acquisition. And to keep customers engaged, they offer enticing bonuses, odds boosts, and prop bets.

Retail sportsbooks price their odds conservatively and often use third-party odds providers. While some retail books do run internal models and accept sharp action in limited markets, they closely monitor winning players.

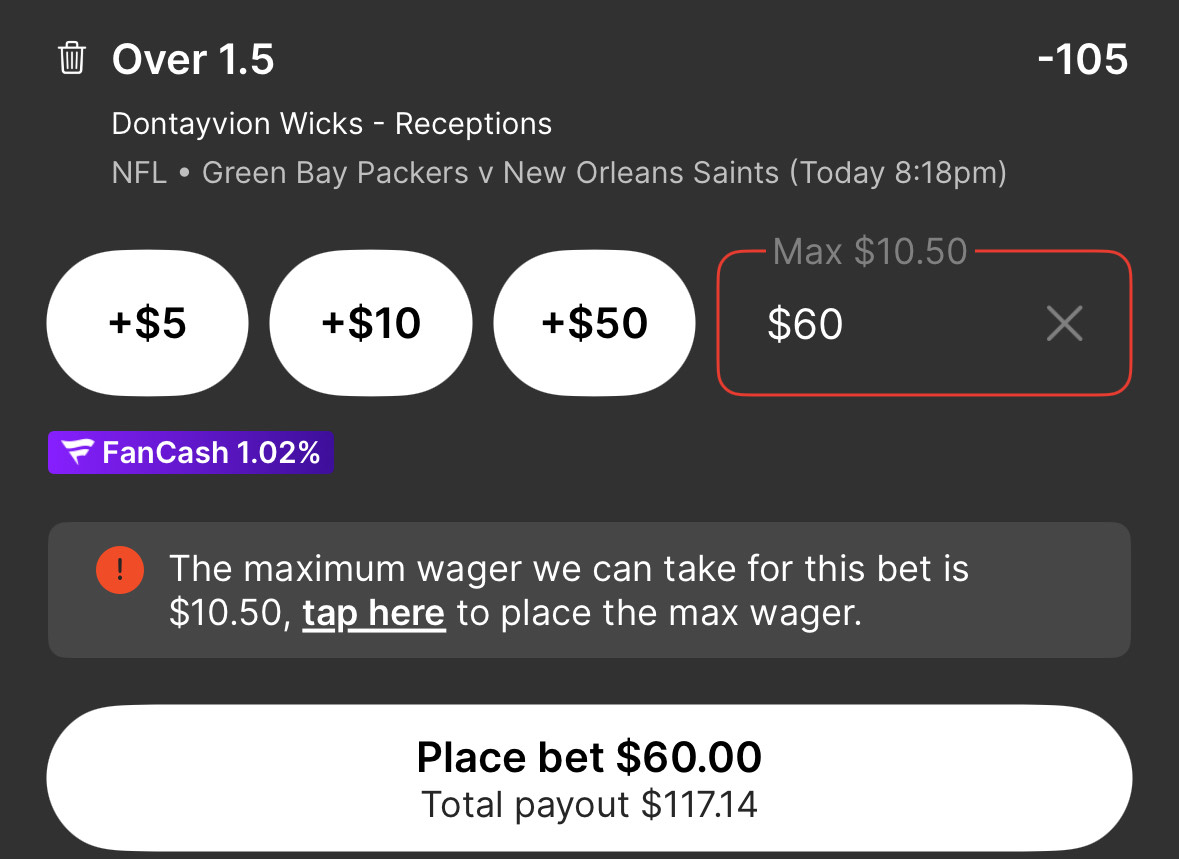

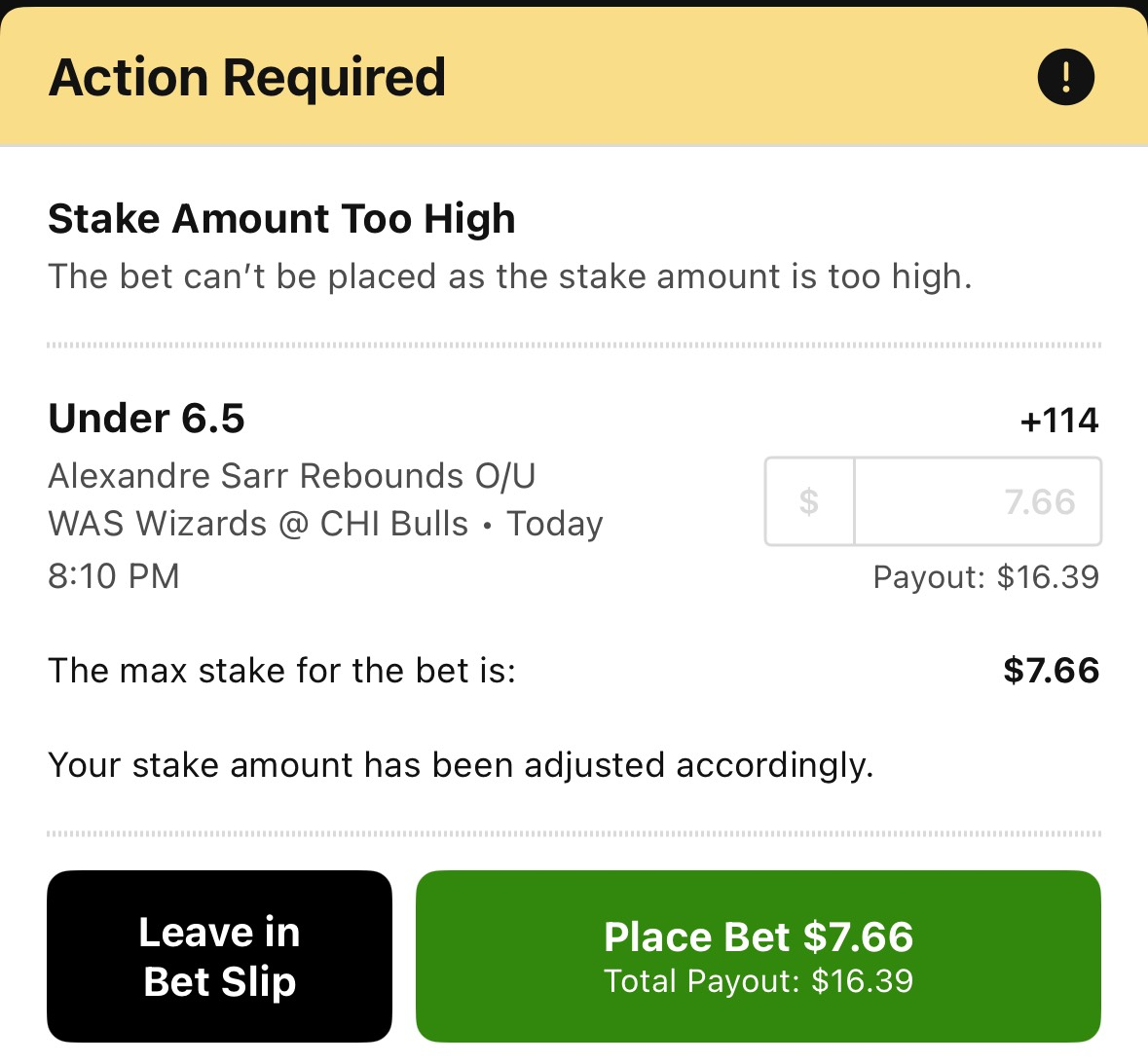

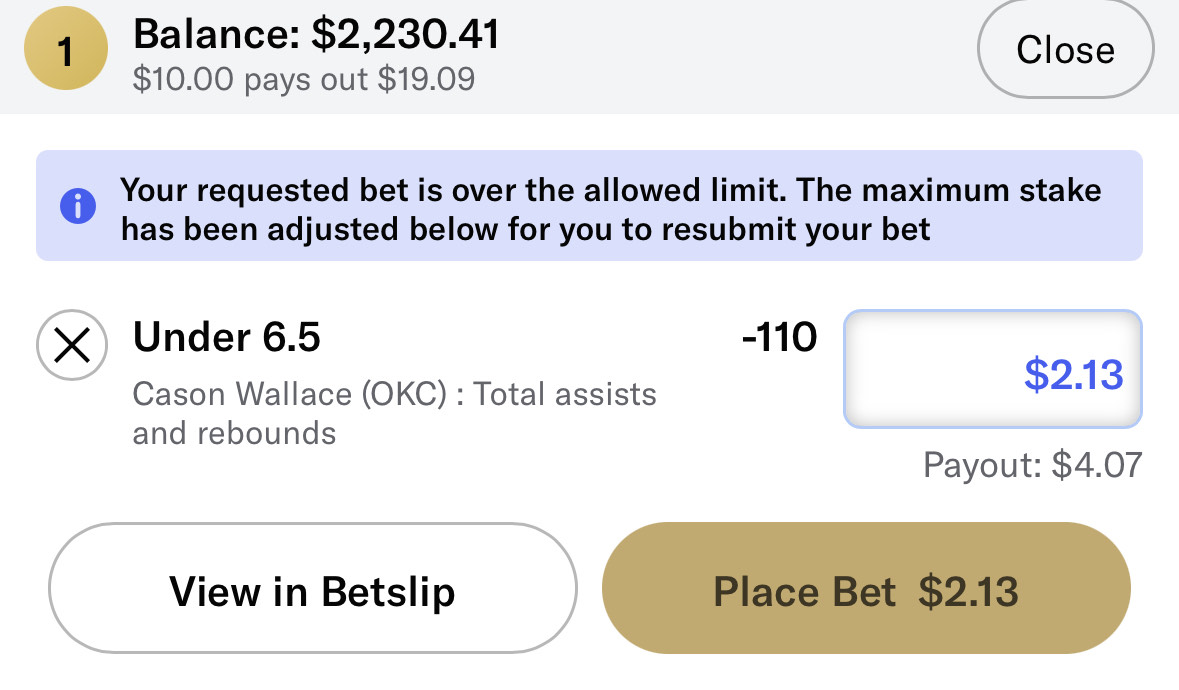

Once a bettor demonstrates consistent profitability, retail sportsbooks typically respond by limiting bet sizes. In my experience, I’ve been restricted to \(\$10\) or less per bet on several major platforms:

The most well-known retail sportsbooks include:

- FanDuel

- DraftKings

- BetMGM

- Caesar’s

- Fanatics

- BetRivers

In summary, retail sportsbooks are where most inefficiencies live, but they also impose the strictest limits on winning players.

Betting Exchanges

Betting exchanges operate differently from traditional sportsbooks. Instead of betting against the house, bettors trade directly with one another. The exchange simply facilitates these trades and charges a small fee, meaning its business model prioritizes betting volume, not bettor losses.

This structure allows exchanges to offer highly competitive odds and avoid limiting winning players. However, exchange prices depend heavily on market liquidity, and on who is providing that liquidity.

An exchange line may look sharp, but without enough volume, it may not reflect true consensus pricing. In thin markets, prices are often set by a small number of participants, many of whom are experienced bettors. This introduces a risk known as adverse selection: when you accept a bet, the person on the other side may be offering it precisely because the price favors them.

A simple example:

Suppose every major sportsbook is offering +100 odds on a coin flip. From this information, you estimate that the coin must be fair: 50% heads and 50% tails. There’s no edge, so you don’t bet.

Now imagine that on a betting exchange, Bettor A offers +115 on heads. Compared to the rest of the market, this looks like clear value. A top-down bettor, Bettor B, spots the discrepancy, assumes the exchange price is mispriced, and takes the +115.

But Bettor A knows something that bettor B doesn’t.

Suppose A receives early information that the coin is slightly rigged, and the true fair price sits closer to +130. Offering +115 is still +EV for A, even though it looks generous relative to other sportsbooks. Bettor B is enticed by the apparent edge, unaware that the bet is still negative EV for anyone without that information.

But if only one or two participants are posting odds, there’s no opposing action to push the price back toward fair value.

This is adverse selection. On a betting exchange, you are the counterparty. In highly liquid markets, prices converge toward fair value. In illiquid markets, attractive looking lines may reflect another sharp bettor’s edge rather than a true mispricing.

Before placing bets on an exchange, always consider the available liquidity and betting limits of the market.

Well-known betting exchanges include:

- ProphetX

- Rebet

- Novig

- Sporttrade

Why does this matter?

For top-down betting strategies, who sets the line is just as important as the line itself.

Market making sportsbooks produce some of the sharpest odds available and are best treated as a reference point for fair pricing. On the other hand, retail sportsbooks post many inefficient odds, but they also react quickly by limiting winning players. Betting exchanges can offer excellent prices, but only when liquidity is high enough to prevent adverse selection.

In practice, sportsbooks don’t fall neatly into one category. For example, FanDuel prices player props very sharply while market makers may be less reliable in these niche markets. Understanding which sportsbooks are sharp in which markets allows you to:

- Identify true pricing discrepancies

- Avoid mistaking adverse selection for value

- Choose the right books to anchor your probability estimates.

Developing this intuition is a meaningful edge on its own. For a deeper breakdown of which sportsbooks tend to be sharp in specific markets, see this article.

Bet Sizing with the Kelly Criterion

After finding a +EV bet, the next question is how much should you bet?

The Kelly Criterion is a formula used in gambling, investing, and trading to determine the optimal fraction of your bankroll to wager in order to maximize long-term growth. While the proof is outside the scope of this post, the intuition is simple: bet more when your edge is larger, and less when it’s smaller.

The Kelly formula is:

\[f = \frac{bp-q}{b}\]where:

- \(f =\) fraction of bankroll to bet

- \(b =\) decimal odds of the bet (What are decimal odds?)

- \(p =\) probability of winning the bet

- \(q =\) probability of losing the bet (\(1-p\))

When applied correctly, the Kelly formula helps grow a bankroll efficiently.

Fractional Kelly

The key assumption behind Kelly is perfect knowledge of the true probability of winning. In reality, probabilities are always estimates derived from models and market odds.

To account for this uncertainty, most bettors use fractional Kelly, which simply means betting a fixed fraction of the full Kelly recommendation. Common choices are \(1/4\) or \(1/3\) Kelly, though the right multiplier depends on how confident you are in your probability estimate.

Fractional Kelly sacrifices some theoretical growth in exchange for reduced volatility and lower risk of overbetting.

The Steps in Advantage Play

At a high level, advantage betting is just a repeatable loop:

Sign up for as many books as possible

Creating as many accounts as possible ensures you have access to the best available line.Identify +EV bets

Look for wagers where the sportsbook’s implied probability is lower than your estimated probability. In practice, this usually means comparing lines to market makers and shopping for the best price.Size your bets

Use the fractional Kelly criterion to scale your bet size to your edge and confidence.Repeat at scale

Winning sports bettors work with thin margins (I typically have about a \(5\%\) edge) and high variance. You need volume and discipline to let the math show up.

Sports Betting and Beyond

This guide just provides an introduction to the core ideas behind advantage betting, but there are many other ways bettors try to find edges: arbitrage, middling, exploiting correlated parlays, and reacting to market moves. But they all boil down to the same underlying question:

\[\text{Is this price better than it should be?}\]As your bet size grows, the game also changes. The challenge shifts from finding +EV bets to getting enough money down before limits or liquidity become the bottleneck.

What I find most interesting about betting markets is that they turn messy real world questions into probabilities. That idea extends well beyond sports. Election betting markets, for example, have historically been remarkably accurate predictors of outcomes, often outperforming traditional polling. During the 2024 election, I followed odds on platforms like Polymarket. If you’re curious about how accurate election markets have been historically, check out this track record.

Markets teach us how to think probabilistically, identify inefficiencies, and manage risk. Even amid uncertainty, patterns and opportunities emerge for those who know where to look.